As a sweeping judicial shake-up weeds out corrupt officials, Albania’s reputation as a place to do business is gradually improving

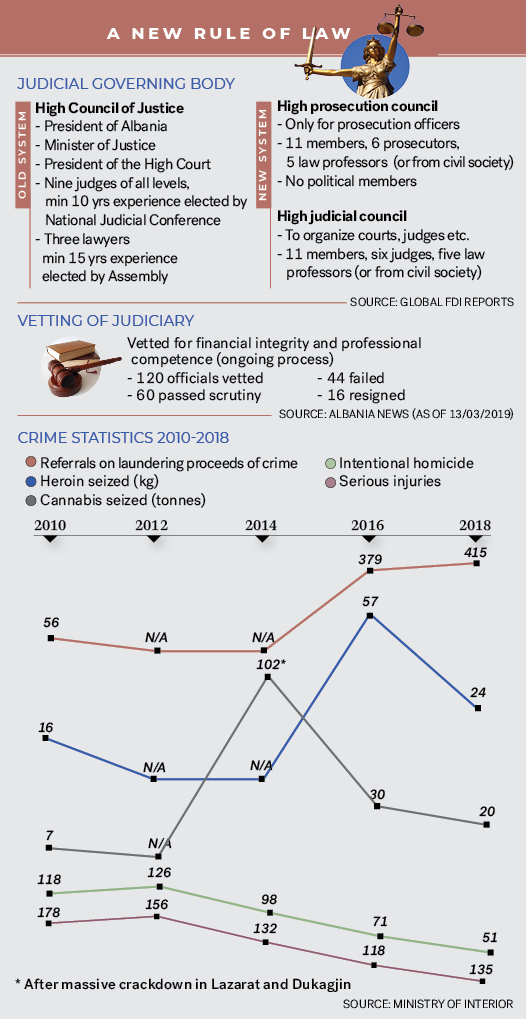

In its desire to accede to membership of the European Union, Albania has been working hard to clean up its judicial act. All prosecutors and judges are now subject to independent and rigorous vetting of suitability for their jobs with specific focus on asset declaration, integrity and professionalism. The results so far show a clear-out rate of half – 40 percent of those vetted were fired and 10 percent resigned. “With so many people fired, the situation is delicate and we guarantee due process for those who are dismissed,” said Albanian Justice Minister Etilda Gjonaj.

With advice over the past three years from the European Commission and individual European countries, Albania has created a twin structure for choosing and overseeing the judiciary. Apart from setting up separate councils for judges and prosecutors, the system seeks to avoid external establishment pressures by excluding politicians from both bodies.

A new law enforcement agency along the lines of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) will be established to handle lawbreaking by politicians and people in senior positions. Its other main function will be to tackle organized crime, which some observers claim is being partially exported rather than eradicated.

The reform program has taken on board ideas from actual and potential investors, who said fighting corruption and organized crime were their main priorities.

“We have strengthened our mechanisms for fighting corruption, and not only in the justice system. We have established an institutional task force that carries out administrative investigations in different agencies and offers services to businesses. When we speak with German investors nowadays, they are pleasantly surprised by the results we are achieving,” Gjonaj added.

While offenses at home are declining, the country’s reputation is still suffering as its criminals expand to neighboring countries

When Albania opened its borders in 1991, tourists came in and citizens left for countries until then denied to them. Among those exiting were criminals intent on expanding their activities.

Returning criminals had often become more sophisticated after mingling with gang bosses abroad, so the job of containing organized crime became more difficult. “Organized crime is not Albanian. It is international,” said Albanian Interior Minister Sander Lleshaj. “We sent liaison officers to several EU states, and we host their officers so we can act together.” Although Albania is frequently branded as in the grip of gangsters, the cooperation has borne fruit. For example, the amount of cannabis seized in Italy coming from Albania dropped by 81 percent between 2017 and 2018.

Organized criminals are also involved in illegal migrants crossing through Albania into Europe. “Using Albania to reach the EU is a concern. We are reducing the numbers by 30 percent a year but we have to stop it completely.”

Despite the odds, the police are increasing confiscation levels from drug traffickers and other criminal networks as well as reducing rates of murder and serious assault.